Which came first - the black hole or the galaxy? Many large galaxies in the Universe have a supermassive black hole at their centre. But which came first? The black hole that is frantically consuming the matter around it or the vast galaxy that is its home?

A European team led by David Elbaz from CEA-IRFU's Astrophysics Department has just discovered a spectacular interaction between a quasar and a galaxy from observations made with the VISIR camera. The camera was built at CEA-IRFU and installed on the European Southern Observatory's (ESO) Very Large Telescope in Chile. A jet from the quasar is responsible for star formation on a large scale in the galaxy (see animated view). From these observations, a new scenario seems to be emerging: black holes might "build" the galaxy that will become their home. This surprising discovery is published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics on 30 November 2009.

The chicken and the egg

"The question of which came first, the chicken or the egg, a galaxy or the black hole at its center, is one of the most hotly debated subjects in Astrophysics today,” says lead author of the study, David Elbaz. Our study suggests that supermassive black holes can trigger a surge of star formation, or even create whole new galaxies. This missing link may help us to understand why galaxies that host the largest black holes also have the most stars."

The naked quasar's enigma

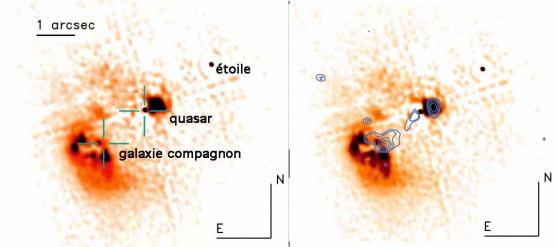

The team's conclusions are based on careful observation of a very peculiar object, the quasar HE0450-2958, located at a redshift distance of about 3,2 billion light-years from the Earth. The term "Quasar", or "Quasi-star" (also known as "QSO" or "Quasi-Stellar Objects"), refers to the core of a galaxy formed by a supermassive black hole. Its center is intensely bright, eclipsing the galaxy that surrounds it. But to date, no host galaxy has ever been detected for the quasar, HE0450-2958, commonly known as "the naked quasar" for this reason. Believing that the host galaxy might be hidden behind large amounts of dust, the astrophysicists used the mid-infrared camera VISIR built by the CEA-Irfu and installed on the ESO's Very Large Telescope (VLT). What they actually observed is far different from their original expectations, but something much more surprising: they did not detect any dust clouds. Instead, they discovered that the nearest galaxy to the quasar has been producing stars at an astounding rate.

Image around the quasar HE0450-2958, at a redshift distance of about 3,2 billions light years from Earth. Left, the image in visible light, obtained by the ACS camera of the Hubble Space Telescope, does not show any galaxy around the quasar but only a very nearby companion galaxy. Right, the contours of the infrared light intensity (at 8.9 microns), measured by the VISIR camera at the VLT telescope (Chile), are superposed on the visible image. The important infrared emission of the companion galaxy, located in the direction of the jet, reveals an important starburst induced by the quasar. Credit CEA/SAp

Starburst induced by the quasar's jet

Although there is not a trace of a star in the area immediately surrounding the quasar, this "companion" galaxy is extremely rich in very young, very bright stars: stars form within it at a rate of approximately 350 Suns a year, a hundred times faster than in a typical galaxy in the Local Universe.

The astrophysicists also discovered a "bridge" of matter between the quasar and its companion galaxy: matter appears to be streaming out of the quasar's black hole towards this galaxy at very high speed. The high-energy injection of this matter into the galaxy suggests that it is the quasar itself that is causing this surge of star formation. If this is the case, the galaxy would have evolved from a cloud of gas hit by the jet of highly energetic particles emerging from the quasar.

Composite image of the quasar HE0450-2958 with visible light emission (shown in yellow, by Hubble, NASA's space telescope) and in the mid-infrared (shown in blue, by the VISIR camera of the ESO's Very Large Telescope). The bridge of infrared light and matter can be seen linking the quasar (in the middle of the picture) and the nearby galaxy (bottom left-hand corner).

See animated view. Credit: ESO.

"The ‘naked quasar’ and its companion galaxy are bound to merge in the future," David Elbaz explains: "the quasar is moving at a speed of only a few tens of thousands of km/hour with respect to the galaxy and the two objects are only about 22,000 light-years away from each other. Whether or not the quasar is 'naked', it will eventually be "dressed" when it merges with its companion galaxy, the stars in which have mostly been formed by the quasar."

These observations change our understanding of this type of system and allow us to develop a new paradigm. The quasars may help to build the galaxy that will later host them. Perhaps this is the missing link that will explain why the mass of black holes is always larger in galaxies that contain the highest number of stars.

The astrophysicists will now search for similar objects in other systems. Future generations of instruments, including the James Webb Space Telescope, operated by NASA/ESA, or Alma, the international millimetric and submillimetric interferometer ALMA (Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array) and the E-ELT (European Extremely Large Telescope) in which the Astrophysical Department of CEA-IRFU and a number of INSU-CNRS teams are involved, will make it possible to study objects like this that are much further away with a great deal more precision, in the bid to uncover a possible link between the formation of supermassive black holes and galaxy formation in the distant Universe.

Contact:

"Quasar induced galaxy formation: a new paradigm?"

D. Elbaz [1] , K. Jahnke [2] , E. Pantin [1] , D. Le Borgne [3] , and G. Letawe [4]

[1] Service d'Astrophysique CEA-Irfu, Laboratoire AIM, CEA/DSM-CNRS-Université Paris Diderot

[2] Max-Planck-Institut für Astronomie, Heidelberg, Germany

[3] UPMC Univ. Paris 06, UMR7095, Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris

[4] Institut d'Astrophysique et Géophysique, Université de Liège, Belgium

published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics on 30 November 2009

electronic version  (format PDF)

(format PDF)

- see: the CEA press realease (30 November 2009)

the ESO press release (30 November 2009)

"The Quasar That Built a Galaxy" published in Science (1 December 2009)

- also see: A new galaxy formation theory (22 January 2009, in french)

No more starless galaxies? (15 November 2007)

A fossil record of galaxy encounters (11 April 2003, in french)

Written by: Jean-Marc Bonnet-Bidaud, D. Elbaz, M. Vandermersch

• Le Département d'Astrophysique // UMR AIM (DAp)

• Cosmology and Galaxy Evolution group (LCEG)

• VISIR