UPDATE [03/26/2024]: The optics de-icing procedure has been a success!

UPDATE [03/26/2024]: Euclid’s optics de-icing procedure has produced much better results than expected. The main suspect in the blurred vision of Euclid’s VIS instrument was the coldest mirror behind the telescope’s main optics. After warming it by just 34 degrees, from -147°C to -113°C, was enough for all the icy water to evaporate. Almost immediately, Euclid regained its sight with 15% more light from the Universe! Scientists and engineers were thus able to determine precisely where the ice had formed, and where it was likely to form again. Find out more on the ESA page.

A few layers of water ice – with the width of a DNA strand – are beginning to affect Euclid‘s vision; a common issue for spacecraft in the freezing cold of space, but a potential problem for this highly sensitive mission that requires remarkable precision to study the nature of the dark Universe. After months of research, Euclid’s teams across Europe, including CEA-Saclay, have devised a new procedure designed to defrost the mission’s optics, which involves independently heating the mirrors. The campaign unfolded as planned, and while it’s still too early to definitively establish its effectiveness, preliminary analyses are promising.

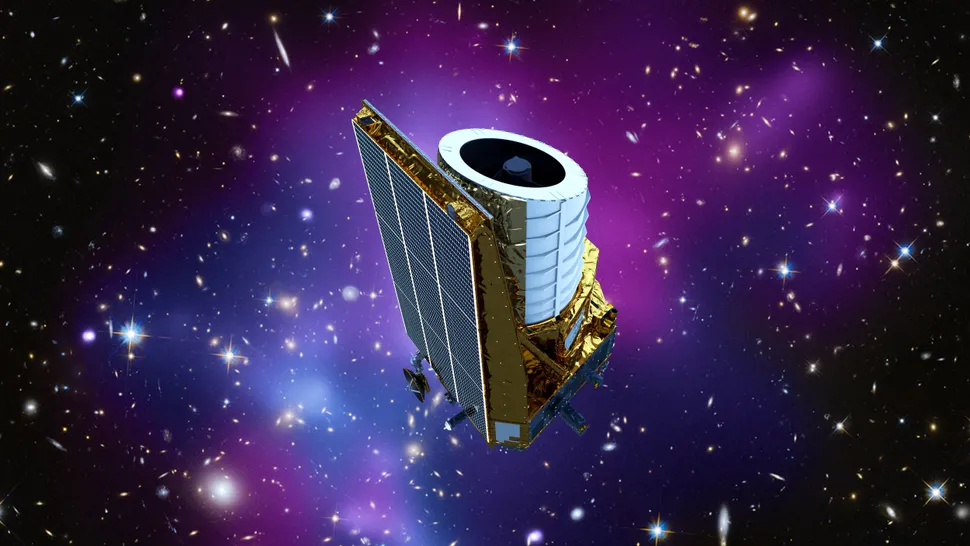

Frost on Euclid’s mirrors

Over the past few months, during Euclid’s fine-tuning and instrument calibration operations, scientists have dealt with various anomalies (such as stray light, X-ray flashes, and guiding issues).

A new challenge has emerged: experts have noticed a gradual but significant decrease in the amount of light measured from stars observed multiple times with the visible instrument (VIS), while its infrared counterpart encountered no difficulties.

“We compared the light from stars entering the VIS instrument with the recorded brightness of the same stars at earlier times, observed both by Euclid and ESA’s Gaia mission,” explains Mischa Schirmer, the scientist in charge of calibration for the Euclid consortium and one of the main designers of the new defrosting plan.

This issue is common for spacecraft: water present in the atmosphere and absorbed by certain components during assembly on Earth is gradually released when the spacecraft is exposed to the freezing vacuum of space. These released water molecules tend to adhere to the first surface they encounter – and when they land on the optics of this highly sensitive mission, they can pose a problem.

For this reason, there was a “degassing campaign” shortly after launch where the telescope was heated by onboard radiators and also partially exposed to the Sun, sublimating most of the water molecules present at launch on or very near Euclid’s surfaces. A considerable fraction, however, survived, being absorbed into the multi-layer insulation, and is now slowly being released.

There are probably just a few tens of nanometers of frozen water on Euclid’s optical mirrors, equivalent to the width of a DNA strand, but enough to degrade the instrument’s performance. This attests to the extreme sensitivity of the mission.

A risky operation from 1.5 million kilometers away

Despite the common occurrence of this contamination problem for spacecraft operating in cold conditions, there is surprisingly little published research on the precise manner in which ice forms on optical mirrors and its impact on observations. However, small amounts of water will continue to be released throughout the duration of the Euclid mission, jeopardizing mission results.

Thus, as Euclid’s observations and science continue, teams have devised a plan to understand where ice is located in the optical system and mitigate its impact now and in the future if it continues to accumulate.

The simplest option would be to heat the entire spacecraft for several days. This would clean the optics but could result in deformation of the mechanical structure due to the expansion of certain materials, thereby inducing subtle misalignment of the optics requiring several weeks of fine recalibration.

“Most other space missions do not have such strict requirements for ‘thermo-optical stability’ as Euclid,” explains Andreas Rudolph, Euclid’s flight director at the ESA Mission Control Center. “To fulfill Euclid’s scientific objectives of creating a 3D map of the Universe by observing billions of galaxies up to 10 billion light-years away, over more than a third of the sky, we must maintain the mission incredibly stable – and this includes its temperature. Therefore, turning on the radiators in the payload module must be done with extreme care.“

To limit thermal changes, the trick is to heat part by part based on the results obtained. The team will start by individually heating low-risk optical parts, located in areas where released water is unlikely to contaminate other instruments or optics. They will begin with two of Euclid’s mirrors that can be heated independently.

“One of them is a good candidate for contamination: it is only in the optical path of VIS and not NISP,” explains Hervé Aussel from CEA-Saclay, the scientific lead for the ground segment responsible for Euclid’s data analysis. “However, it is not certain that this is the sole culprit: indeed, red and infrared light is much less sensitive to scattering by ice than blue light. This may explain why NISP sees nothing. Yet we have good indications that scattering is the issue based on some of our measurements.“

If the loss of light persists, they will continue to heat other groups of Euclid’s mirrors, checking each time the percentage of photons they recover.

The campaign unfolded as planned, and while it’s still too early to definitively establish its effectiveness, preliminary analyses are encouraging.

Further reading:

Contact: